Contents

STORY OF THE WORLD: PART I

Our world is a story told by bodies. A body is a place of interaction, a kingdom without hierarchy, a self that is only in relation. To be a body is to have an edge, and on that edge interact with a body-not-your-body. Bodies are a thing made real by touch, and I mean this on a very physical level—observation is key to making particles behave, is key to tamping down quantum diffusion where it might want to strike at our particular reality, and all observation is, at its core, a kind of touch. So, touch is that which makes the world real, and bodies are the things which we touch/are/are touched by. Language modifies that touch; it tells the story of which bodies can perform which touch, which bodies can touch at all. Which are objects without agency, only able to be touched, and which bodies can touch and affect others. The semiotics of the world in which we live govern the kinds of touch we have access to, and the kinds of bodies.

The dominant paradigm of touch in the world is the colonial, patriarchal, heteronormative one, which tells a story of a ‘perfect’ body, one which is, by its nature, untouchable, and thus unreal. This is the aspirational body, the body which has perfect agency, perfect touch power, and yet, paradoxically, must be untouchable. Only the story of it has the ability to interface with the ‘imperfect’. Christian mythology, deeply interwoven into the colonial worldstory, centers the Garden of Eden as the place of this ‘perfect’ body. In Eden, the initial created man was a ‘perfect’ body. One could argue that when woman was created from one of man’s ribs, this ruptured the perfect body—when man had a body-not-his-body to interface with—but the larger narrative waits until woman and man both make contact with the apple from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. This interfacing with a larger, impure worldbody (and in microcosm, woman’s interfacing with the snake, which tempts her into eating the apple and sharing it with man) causes their perfect forms to falter, and they become ‘fallen.’ In Christian mythology, from that point on all human bodies are subject to this ‘original sin,’ all of them infiltrated by the substance of this apple, and thus imperfect, unable to access Eden.

The story of this perfect body ripples through places where this story has prominence—natural history museums, for example, are largely colonial institutions, and thus ally themselves with and reach toward the perfect body. Primarily this is achieved through taxidermy, a way of producing from a once-living body “something finer than the living organism: …its true end, a new genesis” (p21).1 This taxidermied body, kept out of contact with living bodies as much as possible, becomes something out of its time entirely, frozen in an effort to reclaim Eden by forcibly molding the only kind of body that could reside there. Only a body out-of-time, a body without contact, could be suitably ‘perfect.’ Eden itself, when exposed to time—man, when exposed to other bodies—could not remain perfect. These exhibits are still bodies for a stagnant Eden, the only possible perpetuation.

I said touch is a phenomenon between bodies, one that is true on the level of particulates. In my use of the word body, I mean to exclude no piece of material, whether it be tangible or not, mountainous or microscopic. Others, like Jane Bennett, have used the term agent or actant in its place; I mean any thing or force (physical, social, etc.) that interfaces with and affects any other thing or force.2 By which I mean everything that is, as once again, being is physically inherently a state of interfacing, with time if not with any other thing at all. I open up the notion of body to fully appreciate the animacy of all of these bodies and their planes of interaction.

Across many languages, there is a hierarchy of animation endemic to the language itself, and which reflects and governs social hierarchies of animacy. This hierarchy is one that, determines linguistically and socially the way that bodies are permitted to interact with one another—who can act upon whom. This affects the way we construct sentences, which nouns are prone to subject-ness versus object-ness, and which nouns can access which verbs—which bodies can access which kinds of touch. The codified English language, for example, would be more inclined to say I wrapped the blanket around myself, than to say the blanket wrapped itself around me. The latter seems more ‘poetic’ one could say (the matter of poetry is adjacent to all this, and certainly being a poet has helped stretch language to elasticity inside my body, such that the animacy of ‘inanimates’ come easily to hand), because it gives agency to the blanket, something language considers to be inanimate.

This is not just a phenomenon of the English language, and thus of the English-speaking world—studies have been done across languages which reveal a definite hierarchy of animacy which privileges humans above all else, and deanimates incorporeal concepts even further than ‘inanimate objects’.3 Despite its own insistence on the inanimacy of hierarchies themselves, the animacy hierarchy of language acts extensively upon its users, upon those within its range of touch and affect. The ‘perfect’ taxidermied, story-prescribed body is likewise a force of great animacy and acting power.

Human bodies are, often derogatorily, associated with ‘lower’ bodies on this hierarchy, in a sense that blurs the line between metaphor and true interfacing—that is, if you consider those to be distinct. Human bodies of color are associated repeatedly with animals to emphasize a de-animated-ness to those bodies in comparison to white human bodies. Less often in the realm of metaphor, but very frequently in our tangible existence, human bodies of color, human bodies which are considered to be less animate, are in intimate contact with ‘toxic’ chemicals, such as lead and mercury. When these chemicals interface with white human bodies, a crisis is called, but when they interact with human bodies of color, there is far less outcry. Contact with these chemical bodies is irrevocable, and when considering bodies as interacting planes, and assemblages of bodies within and between bodies as the only way of being-within-time, this contact creates a distinct body-assemblage—the human* + chemical body. In Haraway’s language, a cyborg; in mine, a chimera.

Consider again that the world is a story bodies tell each other. Consider too that this story and the telling both have immense power to animate and disanimate, to change subject and object. Consider that most bodies are telling a colonial, patriarchal, heteronormative story, and that is the way in which they are able to interface with other bodies within that story-paradigm. So what can bodies that are 1) not animated by this story or 2) nonexistent within this story do to animate, insinuate, or interface with the bodies under this story?

In Disidentifications, José Esteban Muñoz outlines & explores a strategy that queer bodies of color use to interact with a world wherein their bodies are less animated, if not entirely ignored. He terms this process disidentification, a mode of interfacing with dominant ideology “that neither opts to assimilate within such a structure nor strictly opposes it; …a strategy that works on and against dominant ideology.”4 Disidentification focuses on working simultaneously within and without the world as determined by the majoritarian culture—some of the substance of a queerworld body necessarily has to come from the imperial world body, as there is, as of yet, not enough substance that is Outside. Part of this substance is language, and disidentification can be a way of processing language-bodies—objectified bodies—into otherworldly ones. Necessarily, our new semiotics that I am proposing, likewise our new physics (for me, they are indelible), draws from language that originates in the current world.

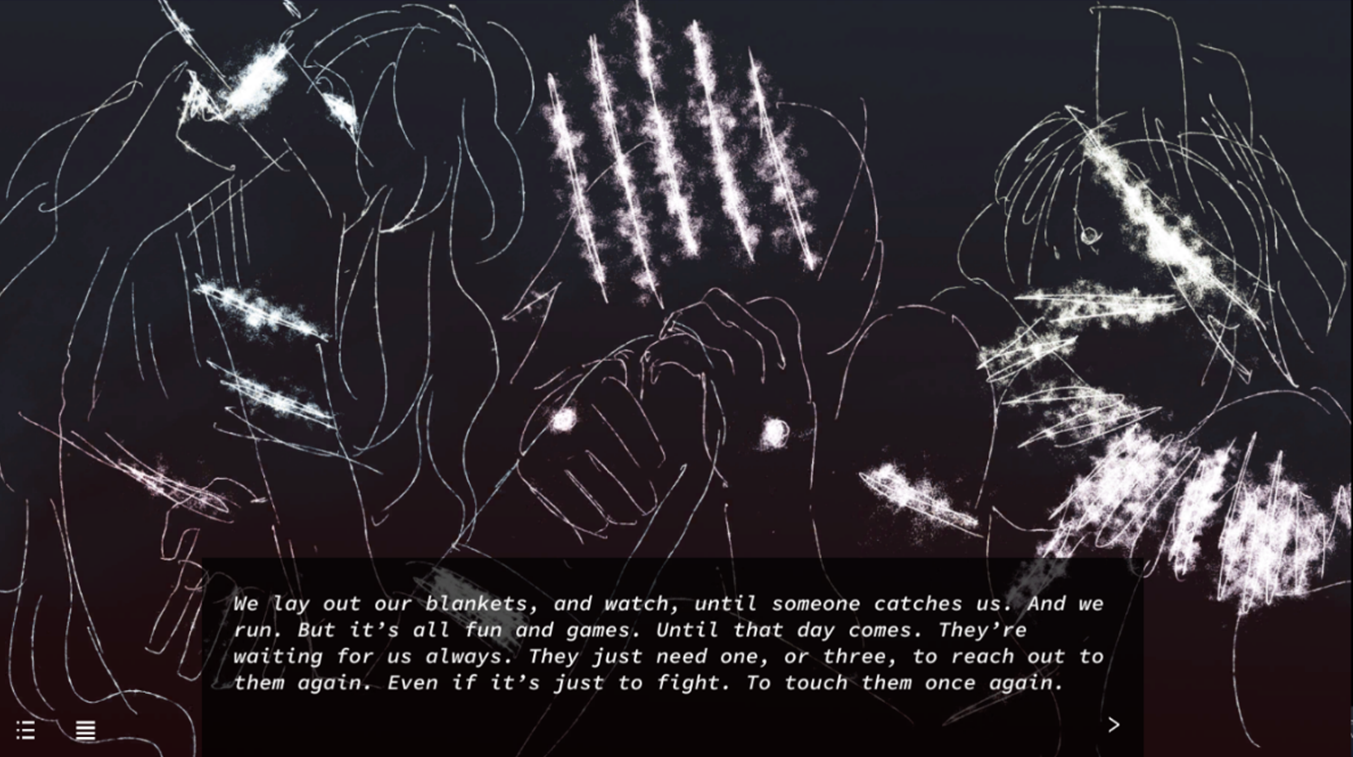

In the formation of this new physics and semiotics, the visual novels of the Worst Girls Games studio have been foundational. Both of their titles, We Know the Devil and Heaven Will Be Mine explore queer bodies navigating the dominant culture that deanimates their bodies and dictates that they interface through violence. While they do take important steps in worldmaking for both non-straight and transgendered bodies, and there are main characters of color in both games, the way their racial identities interface with their queerness and the colonial worldstory is not explored in either. Neither world presents a layer of racial discrimination within their worldstory, but seeing as both visual novels interface with our world/s, which very much do/es have a history of racialization and racialized discrimination and deanimation, this lack is notable. Heaven Will Be Mine, as a visual novel that explores a future in space, also uses the language of space colonization while eliding the point of colonization on Earth and its reverberating affect. Additionally, while it explores in depth the concept of human-to-nonhuman bodies, and the animacy of plastic, electricity, Culture, and gravity, there is not an engagement with other nonhuman forms of matter—repeatedly, the planets that do not have evidence of human interfacing and colonization are referred to as “dead.” Despite these flaws, they are both well worth an exploration, and will serve me well as a springboard for the theory of New Touch.

A key reason to enter a new physics and semiotics is to change the way that one is able to interface with other bodies. Within the animated hierarchy of this worldstory, violence is channeled from more animated bodies into less animated bodies; bodies are able to be designated by this system, able to be contacted by this violence. This transmission is necessary for the bodily practice of sacrifice, which is said channeling of violence. If the sacrificial body is too alien to the sacrificing body, if it operates and exists in a realm where the violence cannot touch, then there can be no effective sacrifice—contact cannot be made through the medium of violence. This is something that both visual novels explore, and something that I think we can reach for, if not at a physical level, as the protagonists of WKTD and HWBM do, at the level of language.

CONT(R)ACTING INHUMAN BODIES: PART II

In We Know the Devil, the first visual novel from Worst Girls Games, the main characters are at a religious summer camp for “bad kids,” and it is expressed in the text that their “badness” is intrinsically related to their queerness.5 Jupiter is stated to have “the best grades in class,” and is “a perfect role model, except for how she always misses the winning goal and she always blanks on the last question.” There is an incompleteness to Jupiter’s “good”-ness, and from the beginning it is connected intimately with touch; a desire to touch and be touched, to hurt and be hurt, as she says during the Red Ending, where she becomes the Devil.

♃: I wasn't born good.

♃: But I still thought I could be.

♃: You know, I actually liked when the captain talked about how heaven was on merit; as long as you do good things, maybe you can one day be good...

♃: But then they said we don't believe in that anymore and it's only what's in your heart that matters.

♃: Just when I thought I got it right, they changed it.

♃: I can try hard, but I think...

♃: God knows my heart isn't really in it.

♃: And that was my only shot, right?

♃: Mom taught me to not touch others. It's just polite, you know.

♃: And dad taught me not to let others touch me. You gotta protect yourself if you're a girl, you know.

♃: But if it's only what I feel inside that matters, what am I supposed to do?

♃: I can't stop that kind of touch.6

This touch is considered to be inappropriate, as queer physical affection has been and continues to be often considered as inappropriate—and as inappropriate physical affection has continued to be associated with queerness. In embracing this touch, in embracing this part of herself, Jupiter becomes the Devil. This Devil-form is a nonhuman queer body, one that is on its way to exiting the semiotics of human sacrificial violence.

However, she is outnumbered by her companions, Neptune and Venus, who are able to destroy her. “There is nothing to fear when there is two against the devil,” the narration says in each regular ending. The story that they are participating in, God’s world, has room for two of them, and room for the Devil to be destroyed, and so through this story they are allowed to make this violent contact with the Devil-body.

There is, however, an ending where this becomes impossible—if all relationships are balanced, so that no one member of the trio is excluded, all three are able to become the Devil. And in this case, there is no one left to stand against her.

THE DEVIL: I know I can't offer much.

THE DEVIL: The bodies I can give you are weak.

THE DEVIL: The stories I tell are impossible.

THE DEVIL: My world is even more precarious than this one.

THE DEVIL: But please come back.

THE DEVIL: It hurts to see you like this so much.

THE DEVIL: So unhappy in those bodies of yours.

THE DEVIL: Stricken by those stories.

THE DEVIL: Forced to live in so much pain.

THE DEVIL: I can't even come save you.

THE DEVIL: But I can promise one thing.

THE DEVIL: There is room for three in my world.

THE DEVIL: And only two in his.7

It is explicitly the story, the semiotic framing of the world that is “God’s,” which is entrapping the three—it is the system of bodies set down by a colonial, patriarchal, and heteronormative society which excludes them by its very nature, by their very bodies.

The Devil here offers a new semiotics, a reality as based on stories as the one in which the player and the three girls inhabit, but one which by its premise is more open in its theory of being. Their bodies physically transform as they become the Devil— Venus tears her old limbs off, and they become a part of a different world. “Someone else’s body now. Not hers,” the narration affirms. Jupiter resists the change at first, afraid of leaving the world which she knows so well, even as it consistently pushes her down despite her efforts at “goodness”.

“I want to leave this camp, this state, this planet. But I can't. I just can't. It’s like a reflex. I can’t stop it,” she says to Venus and Neptune. She asks them to promise that hell is “right there, right behind that door,” that there’s no chance she’ll have to go back to being human. That the queer world, the world where these new bodies are ‘from’ so to speak, the world where they are possible and illegible, at long last, to the world they are leaving, is true, is something they can encounter.

And it is—because of Jupiter’s choice to embrace it. A story can be true if you believe it, and the “three worst girls since Eve” decide to believe, and to become. They reinvent their bodies, and in so doing, invent

the new touch—the feeling of fingers pushing painlessly through our skin, the feeling of the muscle and fat, the weight of it, the intention: it's best friends forever. It's a first kiss. It's a love story.

It’s imaginable, but it doesn’t exist anywhere, not any planet. We're a dream. We're becoming people no other people have ever been. A human that humans are not.8

This new touch is very literal—it’s a new way for bodies to interact, notably separated from the violent paradigm of the world they formerly inhabited. It is also crucial to note that this world exists within this concept of new touch. It does not exist anywhere but in the interaction, in this new relationship between bodies. It is an embrace of relating to bodies, and it means that the Devil, “the shadow of man cast from the light of god,” is no longer alone, no longer severed and bound to interacting with bodies in the ‘real world’ through the violence of her destruction.

The game ends with the narration claiming that the girls have “a new apple…for everyone in the world,” a reiteration of the Fall from Eden, one which is cast in a positive light, as the mode of being unlocked by contact with this new apple is one where “love shines through,” and the mistruths of old bodies are reconfigured into ones which make their bearers happier. A refutation, in the style of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto,” of the Edenic ideal of perfection & original purity—a refutation of origin-as-end.9

Heaven Will Be Mine explores three women also refusing to end where they began—on Earth, subject to Earth’s gravity and Culture.10 HWBM takes place in a world where the space program was expanded to fight a “Cold War” with an alien Existential Threat—but these aliens were ephemeral, unable to be interfaced with in the way of human sacrificial war-violence. So, the space program innovated Ship-Selves, giant plastic robots that could interface with the Existential Threat, because they were designed as toys, designed to operate in a different paradigm of communication. Designed so fighting and fucking, flirting and flying, were no different from one another. With the Existential Threat defeated permanently, however, Earth wishes to ground the spacefarers, because their way of communicating is drifting further and further from that of humanity and is becoming a threat to the solidity of human-ness. Each of the three factions to which our playable pilots belong desires something different for the future of “humanity” in space, and the game has an ending for each of them.

The Memorial Foundation wishes to bring all of humanity back to Earth, “our home, the seat of the universe.” They wish to draw these not-quite-humans back into the fold of Earth’s gravity and Culture—the dominant physics & semiotics of the human body. “Humanity is already the undisputed authority of reality,” Memorial Foundation says in their Return Resolution, “and we have the physics to prove it.” Ultimately, they know this will do one of two things: the pilots will be destroyed by Earth’s Culture and gravity (they will be sacrificed), or they will be warped by it (they will be assimilated, losing a dimension of self). Their argument for bringing them back, despite, is that if they remain, their separation from Earth will mark them as a scapegoat, and they will be killed anyway, in space, by machines of pure, human-determined reality.

Cradle’s Graces is a faction that wants to remain in space and create a new and distinct humanity with an altered set of physics and semiotics, but one that still remains, in its own definition, human.

Matter is made of tiny particles, but enough of it exerts gravity that stitches the universe together. Culture is made of tiny humans, and enough of it together can decide what’s real and what isn’t. It is really quite fucked up that this is how decisions about humans get made. Enough humans can decide anything, and then it’ll be true, even about what’s human and what’s not.

– Internal Communication, Cradle’s Graces Irregulars11

Their goal is to generate enough gravity and Culture to sustain a body of bodies—to build up enough of a language, enough of a cosmic weight, to allow choice and a different way of being human, something that can remain in contact with the old while maintaining its new designation.

The people of Celestial Mechanics wish to have new bodies. They want to merge fully with their Ship-Selves, becoming a different sort of being, a true alien, capable of different kinds of interfacing and communication. The head of Celestial Mechanics, Iapetus, wishes to do this to provoke Earth into scapegoating the remaining pilots—he wishes to “reduce the only information it will be possible to exchange between [the human and the pilots] to violence.” But the pilots themselves, including our playable CM character, Saturn, wants something else for the new ex-humans. A different type of communication, something more in line with what the Ship-Selves were made for—a queer sort of touch.

The Ship-Selves, individually, are designed to generate their own gravity in order to keep their pilots’ bodies intact—they are designed to touch them, to recognize them as a body, and, initially, to recognize them as a human body. The process of Eversion is overloading the tidal reactor, the gravity engine, so that there is no more recognition of separation, so that there is not a human-body and a Ship-Self, but something that was once both but is now neither. Iapetus would have them be able to exchange “matter/light/information without allowing for understanding or communication,” a type of exchange that relies on the human imperial patriarchal heteronormative worldstory, one that does not permit translation across this border, only the transmission of violence. But the Ship-Selves were designed for touch, for communicating. For changing and affirming, for making the not-quite-real just real enough. Saturn changes the worldstory, says “Why should it work like that? Why not make up something different? Who says physics work this way, who says the calculations turn out that way?”

This is an irrevocable change, and an unimaginable one, because ultimately it is impossible for the human to truly conceive of something that is completely alien—we have no frame of reference, and to even imagine it is to touch it, to interface with it, to bring it into contact with the human. And once you can make contact, it cannot be much different from you, can it? The pilots enter their new semiotics and physics through their denial and refutation of the old.

Giving up everything that isn’t real for everything that is. So now they can’t touch each other; can’t lie in bed with each other, can’t get legs entangled with each other.

Instead, they have ways of physically interfacing that aren’t like anything we could imagine. Clouds of particles drift into each other. Maybe they touch through each other instead of just on the surface. It can be in a cold or gentle way, like through a ghost, or maybe a warm and gross way, like reaching into guts. Smiles communicated in physical light, an embrace of psychedelic mind-matter. Lazy sex in a morning bed, except the bed is curvature of space-time and sex is something so obscene it would make your mind implode to consider it.12

This is one of the ways to enter a new world, a new way of interfacing with other bodies, a new definition of body and touch. It may not be possible without such harnessing of gravity. But if you look close enough, and if you want it, you can make it real here, too.

If you side with Cradle’s Graces, humanity truly rends, and Pluto declares war on Earth—but while Earth sends the autonomous military units, those which have only the function to kill that which is human but is not human, the humans of space have their Ship-Selves, their bodies “that can only change others, and never kill… [But] that is the fear of Earth above all else.” Earth fears these not-quite-humans in space, because they are using the word human. And, logically, this means they are able to touch them, to do them harm. Again, the Ship-Selves make this impossible—after the confrontation at the Lunar Gravity Well, they retreat to Venus, whose atmosphere only allows the plastic toy-bodies of Ship-Selves to enter, to make contact. The pilots spend most of their time within their Ship-Selves, and learn to communicate within and between them in ways that differ from those humans in flesh-bodies alone can use. The solar system is “half-real,” as punishment for being unable to reconcile with Earth, half dominated by the Culture and gravity that Earth and its humans cast, and half coaxed along by the whimsy and bodily-driven gravity and care of the pilots in space.

The Cradle’s Graces ending is not an acceptance or a rejection of Earth or humanity; in some ways it is in line with Muñoz’s disidentification strategy. It is finding a way to relate to Earth and its Culture and gravity that is neither destroying it nor accepting it as the only reality. It is finding a way to interface with that system without permanent, sacrificial violence. But it is also not without ritual; it is a transmutation of that violent contact into playfighting. Fighting “like children fight… with bodies of plastic, pretend.” A performative state of being, a performance of rebellion and a performance of war.

The Memorial Foundation ending resonates most strongly with Disidentifications for me, and the most realistic one for those of us who still cannot reach escape velocity. In this ending, the pilots use the Lunar Gravity Well to make the Moon a more stable center of gravity—to “move the center of gravity between the Earth and the Moon,” and in that way, shift the physical law of gravity—altering the fundamental 9.81m/s^2, even if only by 0.01. To change the physics is to change the semiotics, as I have said. The pilots want to bring the space-ness, the ways of being and interfacing that the Ship-Selves have helped them to develop, back down to Earth, to alter in significant way the gravity and therefore Culture there so that they can survive, so that they are not cast out, so that the sacrificial scheme is upset. They want to change the physics, so that they can change reality.

In this ending, the Ship-Selves of our pilots fall apart in the process of making the Moon a livable place—they lose access to those bodies, but the way that they learned to be within them remains. Saturn has a perfect framing of it:

SATURN: All these dreams are meaningful because I’m still human. There’s no way to have everything I want, so I have to choose half. Which is so unfair, you know? I’d rather lose everything trying than get a choice like that. It’s a hard choice, too, the hardest. My human half is so easy to throw out. And so difficult to treasure. Who will be tender with it? Who will see its value? Who will make it powerful? Not me, that’s for sure. I can’t do something like that! If all of you can, you’ve got a lot of work left. It’ll be hard. I know it’s already been much harder for the two of you.

Together, we argue for the value. Let the contamination and change in our bodies grow and thrive. If you want Earth to be our garden, let’s poison it. It will never be the same after we seduce them.13

HWBM’s endings say there is a power in new ways of communication, there is power to change the world by changing little pieces, like a decimal point, or the way bodies can touch other bodies. And if it is possible in Heaven, then, for our sakes, it has to be possible on Earth.

OUR BEAUTIFUL SHAPES: PART III

animacy— The power of a body to act, that is, the power of a body to touch and observe. This is a power held by all bodies, but the bounds of dominant semiotics often privilege some bodies over others in terms of touch-power, and often limits the kinds of touch, some bodies may use to interface.

Culture— The story we tell ourselves, the story that makes the world. That which sets the parameters of bodily interfacing. Equivalent, broadly, to semiotics, or, the language of the world-story. It is the paradigm that bodies operate within. It can be layered, can be undermined by bodies of bodies. There are stories within stories. I am telling you one now.

body— Everything that touches and can be touched. Like Culture, is layered, bodies within bodies within bodies. Down to the smallest thing. But even then, maybe there are bodies we cannot see within them. Bodies have boundaries which separate them from other-bodies, but these boundaries are also the point of interaction between bodies, which is the thing that makes them real. Touch is what makes us real.

gravity— A physical & metaphysical force. On a physical level, draws bodies closer together, based upon their relative mass. On a metaphysical level, is equivalent to atmospheric pressure in its ability to observe bodies.

observation— The touch that makes bodies real, which makes them one-thing, which tells them the story of their related existence. All touch is observation, if you think about it.

physics— Similarly to Culture/semiotics, a paradigm of interactions between bodies, a set of observed rules & behavioral patterns. It is just a language, like any other, and is susceptible to Culture and its way of speaking about bodies. When it gets down to it, though, if one reads the physics alone, the playing field of bodies seems more even.

sacrifice (scapegoat)— A body designated as a sink for violence, a body with whom interfacing with violence is acceptable, and considered to be the only way of interfacing. A body which can accept this violent contact and through ritual transformation purge it. This transformation often transforms the sacrificial body itself, sometimes into a dead body, but not necessarily. Some forms of purging sacrificial violence involve the sacrifice becoming a post-sacrificial body, something so changed it becomes incommunicable to those of the original community.

Here is the object: to become unsacrificeable, to change the way that you can touch, and be touched. To transform violence from the level of language, and from the level of language, transform physical reality. Here is the beginning: tell yourself that it is true. A language is not one person, a body is not ever in isolation, but it is never just you who wants to believe. You can make a start, though, and maybe others will follow you to the other side of language, to the other side of human.

Hell or Heaven, right behind that door. A promise you have to make yourself. No wrong way to do this, as long as you are willing to put the work of transformation in. It is a powerful tool, and something that starts with the tips of your fingers. The edge of your tongue. It is not waiting for us. It is waiting for us to make it.

1. Donna Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936,” Social Text, no. 11 (1984): 21, https://doi.org/10.2307/466593.

2. Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

3. Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), 25-27.

4. José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 11.

5. Worst Girls Games. We Know the Devil. Pillow Fight. PC/Mac. 2015.

6. Worst Girls Games. WKTD.

7. Worst Girls Games. WKTD.

8. Worst Girls Games. WKTD.

9. Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Manifestly Haraway, 3–90. (University of Minnesota Press, 2016) http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1b7x5f6.4.

10. Worst Girls Games, Heaven Will Be Mine. Pillow Fight. PC/Mac. 2018.

11. Worst Girls Games. HWBM.

12. Worst Girls Games. HWBM.

13. Worst Girls Games. HWBM.

* Human being the title given to an assemblage of many interacting bodies which we would consider, separately, to be nonhuman!

Bibliography

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012.

Haraway, Donna, and Cary Wolfe. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Manifestly Haraway, 3–90. University of Minnesota Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1b7x5f6.4.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” Social Text, no. 11 (1984): 20–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/466593.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Worst Girls Games (Aevee Bee and Max Schwartz). We Know the Devil. Pillow Fight. PC/Mac. 2015.

Worst Girls Games (Aevee Bee and Max Schwartz). Heaven Will Be Mine. Pillow Fight. PC/Mac. 2018.

nemo o. captain

n. o. captain writes weird faerie prose, bizarre & unsettling poetry, and occasional essays.